Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

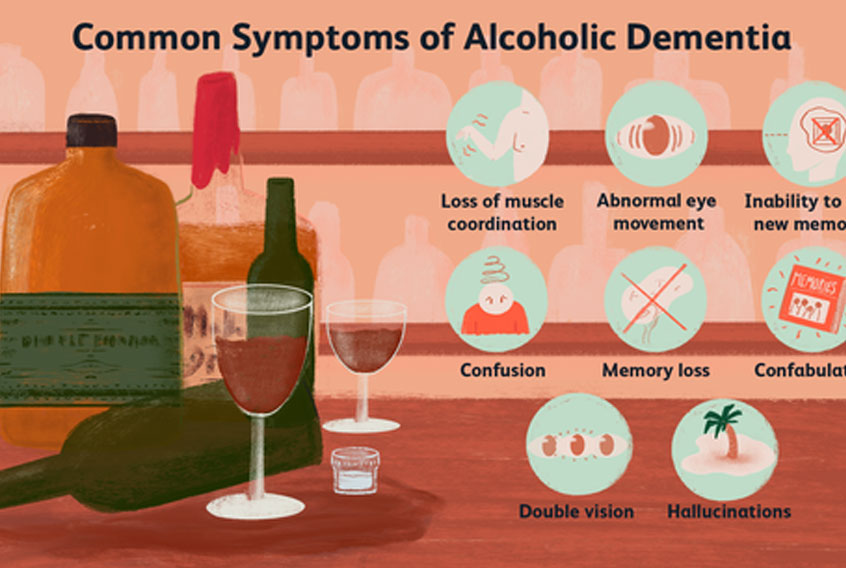

When persistent learning and memory deficits are present in patients with Wernicke encephalopathy (a clinical triad of confusion, ataxia, and nystagmus [or ophthalmoplegia]), the symptom complex is often called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Clinically, this term is best conceptualized as 2 distinct syndromes, with one being characterized by an acute/subacute confusional state and often reversible findings of Wernicke encephalopathy and the other by persistent and irreversible findings of Korsakoff dementia.

In 1881, Carl Wernicke first described an illness that consisted of paralysis of eye movements, ataxia, and mental confusion, in 3 patients. The patients, 2 males with alcoholism and a female with persistent vomiting following sulfuric acid ingestion, exhibited these findings, developed coma, and eventually died. On autopsy, Wernicke detected punctate hemorrhages affecting the gray matter around the third and fourth ventricles and aqueduct of Sylvius. He felt these to be inflammatory and therefore named the disease polioencephalitis hemorrhagica superioris.

SS Korsakoff, a Russian psychiatrist, described the disturbance of memory in the course of long-term alcoholism in a series of articles from 1887-1891. He termed this syndrome psychosis polyneuritica, believing that these typical memory deficits, in conjunction with polyneuropathy, represented different facets of the same disease. In 1897, Murawieff first postulated that a single etiology was responsible for both syndromes

Etiology

A deficiency of thiamine (vitamin B-1) is responsible for the symptom complex manifested in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, and any condition resulting in a poor nutritional state places patients at risk. Heavy, long-term alcohol use is the most common association with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Alcohol interferes with active gastrointestinal transport, and chronic liver disease leads to decreased activation of thiamine pyrophosphate from thiamine, as well as a decreased capacity of the liver to store thiamine.

Thiamine is absorbed from the duodenum. The body has approximately 18 days of thiamine stores. Thiamine is converted to its active form, thiamine pyrophosphate, in neuronal and glial cells. Thiamine pyrophosphate serves as a cofactor for several enzymes, including transketolase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, and alpha ketoglutarate, that function in glucose use. The main function of these enzymes in the brain is lipid (myelin sheath) and carbohydrate metabolism, production of amino acids, and production of glucose-derived neurotransmitters.

Thiamine appears to have a role in axonal conduction, particularly in acetylcholinergic and serotoninergic neurons. A reduction in the function of these enzymes leads to diffuse impairment in the metabolism of glucose in key regions of the brain, resulting in impaired cellular energy metabolism.

Within 2-3 weeks of decreased intake and thiamine depletion, areas of the brain with the highest thiamine content and turnover will demonstrate cellular impairment and injury. The main consequence of these metabolic changes is the loss of osmotic gradients across cell membranes. The earliest biochemical change is the decrease in ?-ketoglutarate-dehydrogenase activity in astrocytes.

Additional findings include increased astrocyte lactate and edema, increased extracellular glutamate concentrations, increased nitric oxide from endothelial cell dysfunction, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation in neurons, free radical production and increase in cytokines, and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Thiamine appears to have a role in acetylcholinergic and serotoninergic synaptic transmission and axonal conduction.

Symptoms of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome are attributed to these focal areas of damage. Ocular motor signs are attributable to lesions in the brainstem affecting the abducens nuclei and eye movement centers in the pons and midbrain. These lesions are characterized by a lack of significant destruction to nerve cells, which accounts for the rapid improvement and degree of recovery observed with thiamine repletion.

Ataxia is a manifestation of damage to the cerebellum, particularly the superior vermis. The cerebellar changes consist of a degeneration of all layers of the cortex, particularly the Purkinje cells. The loss of neurons leads to persistent ataxia of gait and stance. In addition to cerebellar dysfunction, the vestibular apparatus is also affected. In addition, chronic alcohol consumption results in a 35% decrease in transketolase activity within the cerebellum, which is likely due to thiamine deficiency.

Vestibular paresis, confirmed by abnormal results on caloric testing, is observed in the early stages of disease and generally improves with treatment. The amnestic component is related to damage in the diencephalon, including the medial thalamus, and connections with the medial temporal lobes and amygdala. The slow and incomplete recovery of memory deficits suggests that amnesia is related to irreversible structural damage.

McEntee and colleagues demonstrated decreased levels of a metabolite of norepinephrine (3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenolglycol, or MHPG) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of some patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. They pointed out that the diencephalic lesions are located within monoamine-containing pathways. Clonidine, an alpha-noradrenergic agonist, seemed to improve the memory disorder of their patients. They postulated that damage to these pathways may be the basis for the amnestic features of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. These results have not been reproduced in any large prospective study. Patients with permanent Korsakoff psychosis are not routinely treated with clonidine.

Variations in clinical presentations and the fact that not all patients with thiamine deficiency develop Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome has raised the possibility that a genetic predisposition may exist in some patients. Some patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome demonstrate a decreased affinity of transketolase for thiamine pyrophosphate. The mechanism behind this difference in the biochemical activity of transketolase in not fully understood.

Variants in the gene coding for the high-affinity thiamine transporter protein SLC19A2 in neurons may also contribute to the susceptibility of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Patients with a functional impairment in the ability to effectively transport thiamine may have impaired ability to cope with thiamine deficiency or respond to thiamine replacement.

The following are causes of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome:

* Chronic alcoholism

* Nutritional deficiency

* Starvation – Persons with anorexia nervosa, schizophrenia, or terminal cancer ; prisoners of war

* Thiamine-deficient formula

* Hyperemesis gravidarum – In a study of 49 cases of Wernicke encephalopathy in pregnancy, pregnancy loss attributable to Wernicke encephalopathy was nearly 48%

* Gastric malignancy

* Intestinal obstruction

* Bariatric surgery – Wernicke encephalopathy can present as early as 2 weeks after surgery; recovery typically occurs within 3-6 months of initiation of therapy but may be incomplete if this syndrome is not recognized promptly and treated (the highest risk is in young women with vomiting)

* Systemic diseases – Malignancy, disseminated tuberculosis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), uremia

* Iatrogenic – Intravenous hyperalimentation, refeeding after starvation, chronic hemodialysis

Prevention of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

If you eat a well-balanced, healthy diet and do not abuse alcohol your chances of developing Wenicke-Korsakoff are virtually nonexistent, unless you have a malabsorption problem.

As a considerable number of alcohol-dependent individuals are unable to stop drinking, such as homeless drinkers, some say alcoholic drinks should be supplemented with thiamin.

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Long-standing alcohol use is the most common association with development of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, although poor nutrition can also be an important factor. Prevalence data have come primarily from necropsy studies, with rates of 1-3%, and have indicated that prevalence at autopsy exceeds clinical detection. The rate has been found to be significantly higher in specific populations, ie, homeless people, older people (especially those living alone or in isolation), and psychiatric inpatients, where alcohol use and poor nutritional states predominate.

International occurrence

International and US rates of occurrence are essentially the same. In a survey of neuropathologists from several countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, Norway, United Kingdom, United States), prevalence ranged from 0-2.8%. Prevalence did not correlate with per capita alcohol consumption in each country.

Sex- and age-related demographics

The condition affects males slightly more frequently than it affects females. Age of onset is evenly distributed from 30-70 years.

What Is Wet Brain?

Wet brain is a form of brain damage. Wet brain is also called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, Korsakoff’s psychosis, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, and beri beri. The symptoms of wet brain may sometimes improve with therapy but it is often permanent and irreversible.

Wet brain is caused by a deficiency of thiamine which is also known as vitamin B1. Chronic, heavy alcohol consumption can lead to a thiamine deficiency which can then lead to wet brain. This is because alcohol interferes with the absorption of thiamine. Wet brain can also occur in people who have never consumed alcohol. A diet of nothing but polished rice can cause wet brain because of the lack of thiamine in the diet. Wet brain can also be brought on by periods of vomiting which last for several days such as might result from severe morning sickness or bulimia.

Wet brain is not caused by alcohol killing brain cells. A study by Jensen and Pakkenberg suggests that chronic heavy drinking does not result in the loss of gray matter – the thinking part of the brain – although it can result in the loss of white matter. The exact nature of the impact of chronic heavy drinking on cognitive abilities in well nourished individuals remains something of a matter of dispute.

Wet brain is not a case of gradual brain damage occurring over time – wet brain has a sudden onset and is often brought on by an sudden large dose of glucose in an individual suffering from a severe thiamine deficiency.

Prognosis

Mortality may be secondary to infections and hepatic failure, but some deaths are directly attributable to irreversible defects of severe and prolonged thiamine deficiency (eg, coma).

Ocular complications

Patients who recover generally do so in a particular sequence. Improvement of ocular abnormalities is the earliest and most dramatic, usually occurring within hours of the initial thiamine dose. Failure of ocular abnormalities to respond to thiamine in this manner should raise doubt as to the veracity of the diagnosis.

Vertical nystagmus may persist for months. Fine horizontal nystagmus may persist indefinitely in as many as 60% of patients, but patients completely recover from sixth nerve palsies, ptosis, and vertical-gaze palsies.

Ataxic complications

Approximately 40% of patients recover completely from their ataxic symptoms. The remainder have varying degrees of incomplete recovery, with a residual slow, shuffling, wide-based gait and the inability to tandem walk. Vestibular dysfunction generally responds to a similar degree.

Mental status complications

The symptoms of global confusional state often resolve gradually after treatment is initiated. If an amnestic deficit is present, it will manifest as the early signs of apathy and global confusion resolve. Only 20% of patients who demonstrate signs of the amnestic state after treatment has been initiated have complete recovery. The remaining patients have varying degrees of persistent learning and memory impairment.

Maximum recovery may take 1 or more years and depends on abstinence from alcohol. According to reports, once patients with Korsakoff psychosis have recovered, they do not demand alcohol, but they will accept it if offered.

Mortality

The mortality rate is up to 10-15% in severe cases. Since the presentation is variable and often clinically missed, the exact mortality rate is difficult to estimate. Prognosis depends on the stage of disease at presentation and prompt treatment.

Patient Education

In alcohol-related Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, abstinence from alcohol and maintenance of a balanced diet offer the best chance for recovery and prevention of future episodes.

Patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery are recommended to adhere to a balanced diet and continue vitamin supplementation.

Family education and support is an important component of taking care of anyone with a dementia illness, including Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Patients with persistent dementia usually require 24-hour supervision, because they usually have poor insight into their illness and significant functional impairments in activities of daily living. Some patients with alcohol dependence may continue to prefer alcohol use, despite their cognitive deficits. In severe cases, private or public guardianships (or conservatorships) may need to be sought from the courts.

Some helpful web sites for patients include the following:

* Family Caregiver Alliance, Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

* National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome Information Page

* Alzheimer’s Association, Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

###

Author: Glen L Xiong, MD; Chief Editor: David Bienenfeld, MD

###

BOOKS

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition, text revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association,2000.

Hochhalter, Angela K., Whitney A. Sweeney, Lisa M. Savage, Bruce L. Bakke, and J. Bruce Overmier. “Using animal models to address the memory deficits of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.” In Animal Research in Human Health: Advancing Human Welfare Through Behavioral Science, edited by Marilyn E. Carroll and J. Bruce Overmier. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001.

Mesulam, M.-Marsel. Principles of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Nolte, John. The Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Anatomy. 5th edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Walsh, Kevin and David Darby. Neuropsychology: A Clinical Approach. 4th edition. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone,1999.