Frontotemporal Dementia

Based on the distinct patterns of signs and symptoms, three different clinical syndromes have been grouped together under the category of “frontotemporal dementia” (FTD):

Behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

Semantic dementia (SD) and

Progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA).

Previously, researchers sometimes used “FTD” to refer only to bvFTD, which has also been called “frontal variant FTD” (fvFTD) or Pick’s Disease. The language variants (SD and PNFA) are sometimes grouped together under the term “primary progressive aphasia” (PPA). PPA has since been split into three subgroups: progressive non-fluent aphasia, semantic dementia and logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA). At autopsy, patients with LPA are often found to have Alzheimer’s disease, not FTLD. SD was previously referred to at times as “temporal variant FTD” (tvFTD).

A small number of people affected by FTD also develop motor neuron disease (FTD/MND), (sometimes called FTD with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or FTD/ALS).

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), also called corticobasal syndrome or corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) are two related diseases that are not classified as FTD but often share some symptoms with FTD.

Forms of Frontotemporal Dementia

Behavioral variant FTD

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) has also been referred to as “frontal variant FTD” (fvFTD) or “Pick’s disease.” Approximately 60% of people with any form of FTD have bvFTD. By definition, this form of FTD affects social skills, emotions, personal conduct, and self-awareness. Deficits in these functions most often reflect damage to specific regions within the frontal and temporal lobes. With damage to these areas, people may show mood and behavior changes including stubbornness, emotional coldness or distance, apathy and selfishness. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which affects a different area of the brain, many people with bvFTD don’t show any confusion or forgetfulness about where they are or what day it is, at least at first.

Semantic dementia

Semantic dementia, which has also been called “temporal variant FTD,” accounts for 20% of FTD cases. Language difficulty, the predominant complaint of people with SD, is due to the disease damaging the left temporal lobe, an area critical for assigning meaning to words. The language deficit is not in producing speech but is a loss of the meaning, or semantics, of words. At first, you might notice someone substituting a word like “thingy” for more unusual words, but eventually a person with SD will lose the meaning of more common words as well. For example, early in the illness a patient might lose the word for a falcon, later-on forget the word for a chicken, then call all winged creatures “bird” and eventually call all animals “things.” Not only do they lose the ability to recall the word, but the concept of these words is also lost. “What is a bird?” might be a typical response for a patient with advanced SD. Reading and spelling usually decline as well, but the person may still be able to do arithmetic and use numbers, shapes or colors well. Names of people, even good friends, can become quite difficult for people with SD. Like the behavioral variant, memory, an understanding of where they are, and sense of day and time tend to function as before. Muscle control for daily life and activities tends to remain good until late in the disease. Some of these skills may seem worse than they actually are because of the language difficulty people with SD have when they try to express themselves.

When SD starts in the right temporal lobe, people in the early stages have more trouble remembering the faces of friends and familiar people. Additionally, these people show profound deficits in understanding the emotions of others. The loss of empathy is an early, and often initial, symptom of patients with this right-sided form of SD. Eventually people with right-sided onset progress to the left side and then develop the classical language features of SD. Similarly, left-sided cases progress to involve the right temporal lobe and then the person experiences difficulty recognizing faces, foods, animals and emotion. SD patients eventually develop classical bvFTD behaviors including disinhibition, apathy, loss of empathy and diminished insight. The time from diagnosis to the end is longer than for those with bvFTD, typically taking about six years.

Behavioural-variant FTD

In the frontal or behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, the person’s mood and behaviour may become fixed and difficult to change, making individuals appear selfish and unfeeling. A loss of empathy and emotional warmth is very common. In contrast to Alzheimer’s disease, recent memory is typically preserved.

Apathy or lack of motivation is very common, leading people with FTD to abandon hobbies and avoid social contact. Others lose normal inhibitions and start talking to strangers or exhibiting embarrassing behaviour in public.

Difficulty in reasoning, judgement, organisation and planning is frequent, along with a reduction in spontaneous conversation. Changes in eating patterns are very common often with a craving for sweet food, a tendency to overeat and a restriction in food preferences.

A decline in self-care and a reduction in the ability to perform activities of daily living is another early feature. As the disease progresses, the person may become ‘obsessional’, repeating patterns of movement and behaviours like handwringing or echoing back whatever is said.

Semantic dementia

In patients with the temporal lobe form of Frontotemporal Dementia, the initial symptom is usually a decline in language abilities. The left temporal lobe is critical for the fluent production of words and especially for assigning meaning to words. Because the language disorder associated with temporal lobe pathology reflects a breakdown in the meaning (or semantic) system underlying language, we prefer the term semantic dementia which conveys the core deficit and progressive nature of the disorder.

Patients typically complain of a “loss of memory for words” involving, at first, less common words and particularly the names of peoples’. As the disease progresses impairment of word comprehension is noticeable which again affects less common words. Reading and spelling are also typically affected, although numerical abilities can be remarkably well spared.

If the right temporal lobe is involved then patients (or carers) often notice problems recognising previously familiar people. It is not uncommon for patients to talk to people as if they were strangers only to discover later that were old friends.

Day-to-day memory is relatively spared but may appear poor due to difficulty with expression. In later stages, the disease spreads to the frontal lobes so that many of the features listed above, especially the changes in emotional responses, empathy and food preference. We have noticed that many patients with semantic dementia are extremely good at puzzles, bingo and jigsaws, and retain sporting abilities such as bowls or golf until very late in their illness.

Skills associated with posterior brain regions such as navigation, route finding and eye-hand coordination are spared at least until very late in the disease.

Progressive Non-fluent Aphasia

Progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA) is the least common form of Frontotemporal Dementia and affects the ability to speak fluently. Patients present with difficulty communicating due to slow and laboured production of words often with distortion of speech and a tendency to produce the wrong word.

Some patients have slurring of speech whereas others are able to articulate words but produce frequent near misses (e.g. they say “silter” for “sister”). Understanding of word meaning is preserved, but patients with PNFA have problems comprehending sentences and following conversations, especially if there are a number of speakers. Using the telephone and communicating with groups of people is particularly difficult.

Spelling is frequently impaired from an early stage and some patients develop difficulties reading (so called dyslexia). Subtle deficits in problem solving, mental flexibility and decision making are often present from an early stage. Changes in behaviour are uncommon in the early stages but do occur later.

Some people develop clumsiness of handuse, known as apraxia. In later stages, the disease spreads to the frontal lobes, so that many of the features described above, especially the changes in emotional responses and empathy occur. There is considerable overlap between progressive nonfluent aphasia and corticobasal degeneration.

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

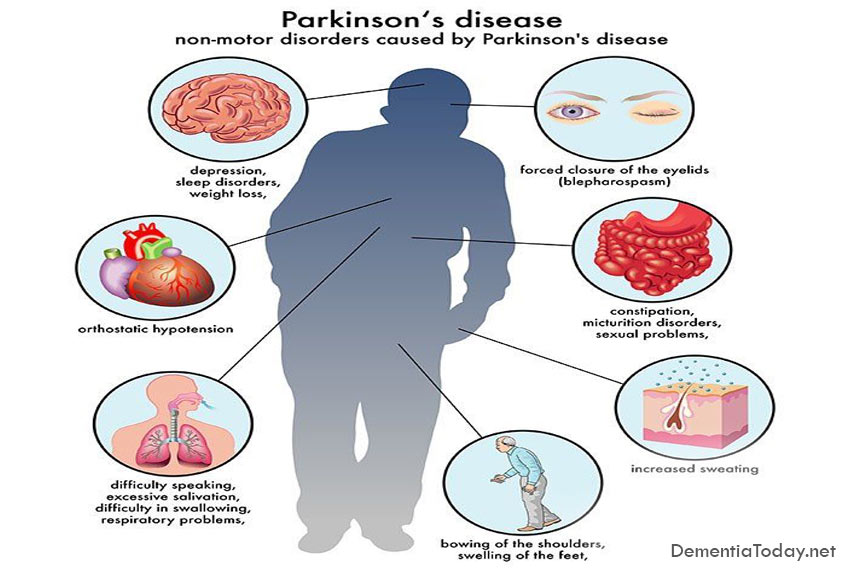

PNFA accounts for only about 20% of all people with FTD. Unlike semantic dementia where the person maintains the ability to speak but loses the meaning of the word, people with PNFA have difficulty producing language fluently even though they still know the meaning of the words they are trying to say. The person may talk slowly, having trouble saying the words, and have great trouble with the telephone, talking within groups of people or understanding complex sentences. In recent years it has become apparent that many patients with PNFA go on to develop severe Parkinsonian symptoms that overlap with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD) such as an inability to move the eyes side-to-side, muscle rigidity in the arms and legs, falls, and weakness in the muscles around the throat.

How Do You Know if it’s FTD?

In trying to determine what is happening to a person, a doctor must first review the important signs and symptoms with the patient and caregivers. Determination of the neuropsychological, neurological, psychiatric, general medical and functional status of the patient is also important. People with FTD are often misdiagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric problems, vascular dementia or Parkinson’s disease. MRI can help rule out other diseases and support a diagnosis of FTD.

The Genetics of Frontotemporal Dementia

Genes are the building blocks of cells, which provides information to enable our bodies to function properly. When one or a number of these genes are abnormal it can lead to the development of diseases such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD). These abnormal genes can be passed down through generations and can affect both males and females.

Genetics is a term that relates to the study of genes and their role in inheritance. When 1 or more close family members have a history of young onset dementia or a related disease (such as Motor neuron Disease), this is known as familial disease and indicates that the disease was passed down through the family line. In FTD, a familial pattern of inheritance has been determined in approximately 15% to 20% of patients. Where there is only a weak indication of family history (such as an elderly relative with dementia), or no other known relatives affected, the presentation of illness is classed as sporadic.

Motor Neurone Disease (MND) is closely related to FTD, and family members of patients with FTD can develop features of MND, FTD or a combination of FTD and MND. This association has been recognised for a number of years but only recently has the genetic evidence for the overlap come to light. In 2011 a gene abnormality on chromosome 9, known as the C9ORF72 genetic mutation, was described. This mutation explains at least one-third of cases of familial FTD as well as a small proportion of sporadic FTD. The presence of this mutation in a small proportion of apparently sporadic cases has important implications for genetic testing, as we can no longer rely totally on family history to determine which patients are at risk of this mutation. Inheritance of this mutation remains to be fully elucidated so although a patient may not have a known family history, we may still consider testing for this mutation.

Two other genetic causes of familial FTD are the Progranulin and Tau mutations (both on chromosome 17) and together with C9ORF72 account for the majority of familial FTD. By performing tests on a person’s DNA (commonly through a blood or saliva sample), it is now possible to identify a mutation in most instances of familial FTD. Both the Progranulin and Tau mutations are Autosomal Dominant with a 50% risk of passing on the mutation to offspring. Major technological advances have been made in genetic screening processes and it seems likely that further genes will be discovered over the coming years as more of the human genome is mapped.

The study of genetics in FTD is valuable for both patients and researchers. Most of the FTD genes are Autosomal Dominant which means that the risk to offspring is 50%. Knowing the mutation status of each patient allows for better management of the illness and identifies potential health implications to both siblings and offspring of the affected person.

When we have a research finding of a genetic change or mutation, the centre has arrangements in place to ensure appropriate referral to a clinical genetics team to confirm the gene mutation and to allow patients and their families to access genetic counselling and predictive testing for those at risk. Genetic counselling is essential to ensure patients and their family members are fully informed regarding risk and implications of finding a mutation, particularly in those who do not express any symptoms of FTD illness.

From a research perspective the study of genetics is vital to help us understand the factors involved in disease development, expression and progression. By further understanding these disease mechanisms it allows accurate information to be made available to mutation carriers and their relatives, and ultimately aids the advancement towards effective drug development.

###

Neuroscience Research Australia