What is frontotemporal dementia?

There is a type of dementia called “frontotemporal” which typically affects patients at a very early age. In this type of dementia, there is no true memory loss in the early stages of the type that is seen in Alzheimer’s dementia. Instead, there are changes in personality, ability to concentrate, social skills, motivation and reasoning. Because of their nature, these symptoms are often confused with psychiatric disorders. There are gradual changes in one’s customary ways of behaving and responding emotionally to others. Memory, language and visual perception are usually not impaired for the first two years, yet as the disease progresses and spreads to other areas of the brain, they too may become affected. Typically, the disorder affects females more than males.

The symptoms reflect the fact that the brain degeneration is not initially widespread and settles in the parts of the brain that are important for social skills, reasoning, judgement and the ability to take initiative.

When the brains of individuals with frontal lobe dementia are studied after death, the types of microscopic abnormalities that are seen are typically of two kinds. The first type is called Non-specific focal degeneration and the second is labeled Pick’s disease. Non-specific focal degeneration accounts for 80% of cases of frontal lobe dementia. It is called “non specific” because there are no abnormal particles that are identifiable-only evidence that brain cells have been eliminated. Pick’s disease, which accounts for 20% of cases of frontal lobe dementia, is identified under the microscope by abnormal particles called “Pick bodies”, named after the neurologist who first observed them.

Comportment, Insight, and Reasoning

Frontotemporal dementia affects the part of the brain that regulates comportment, insight and reasoning.

“Comportment” is a term that refers to social behavior, insight, and “appropriateness” in different social contexts. Normal comportment involves having insight and the ability to recognize what behavior is appropriate in a particular social situation and to adapt one’s behavior to the situation. For example, a funeral is a solemn event requiring certain types of behavior and decorum. Similarly, while it may be perfectly natural and acceptable to take one’s shoes and socks off at home, it is probably not the thing to do while in a restaurant. Comportment also refers to the style and content of a person’s language. Certain types of language are acceptable in some situations or with friends and family, and not acceptable in others.

Insight, an important aspect of comportment, has to do with the ability to “see” oneself as others do. Insight is necessary in order to determine whether one is behaving in a socially acceptable or in a reasonable manner. Insight is also necessary for the patient to recognize his/ her deficits and illness. Changes in comportment may be manifested as “personality” alterations. A generally active, involved person could become apathetic and disinterested. The opposite may also occur. A usually quiet individual may become more outgoing, boisterous and disinhibited. Personality changes can also involve increased irritability, anger and even verbal or physical outbursts toward others (usually the caregiver). Comportment is assessed by observing the patient’s behavior throughout the examination and interviewing other people (family and friends) who have information about the patient’s “characteristic” behavior.

Deficits in frontotemporal dementia

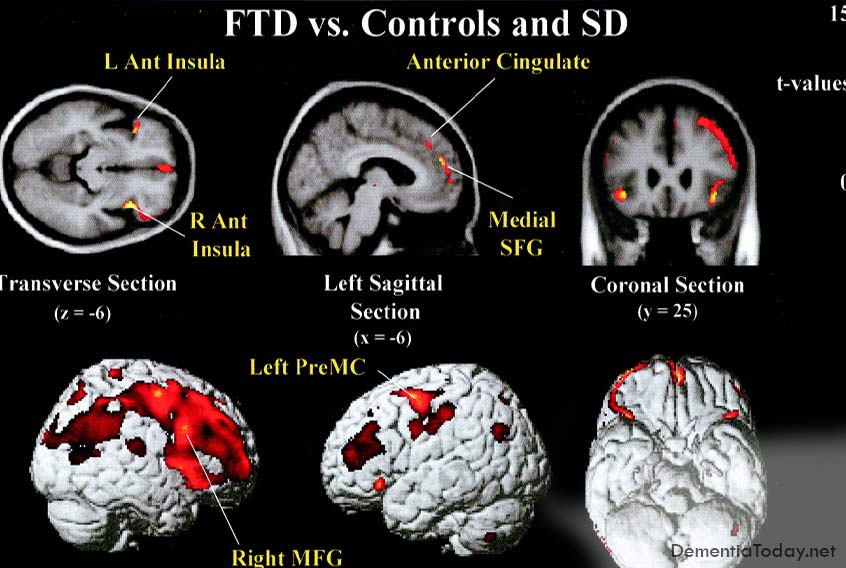

Deficits associated with frontotemporal dementia are varied and depend on the location and severity of pathology in the brain. Most common deficits are changes in behaviour and personality, difficulty relating to other people and difficulty organising day‐to‐day activities. In these patients, the underlying brain changes affect predominantly the frontal lobes (Behavioural- variant FTD). In contrast, other patients show change in language proficiency, either in the form of a difficulty understanding the meaning of words (Semantic Dementia), or a difficulty using the correct words (Progressive Non-fluent Aphasia) . This may be accompanied by a difficulty judging emotional state in self and others accurately. In these patients, the pathology is more pronounced in the anterior portion of the temporal lobe, or in the region where the frontal lobe meets the parietal and temporal lobes. Over time, and as the disease progresses, pathology tends to become more diffuse. As a consequence, clinical presentations tend to merge and deficits become more pronounced.

Managing frontotemporal dementia

Not uncommonly, individuals with frontotemporal dementia show a limited awareness of their deficits in thinking and changes in behaviour and a reduced understanding of the impact of their condition on friends and families. This limited insight may create significant challenges for carers. Although each situation is unique, a number of simple guidelines may be helpful. First, carers need to recognise that behavioural changes are the result of changes in the brain. In most instances, the person is not being difficult intentionally. As such, direct confrontation to change a difficult or inappropriate behaviour is unlikely to be successful. You are more likely to succeed by changing the environment, for example by redirecting attention or removing what triggered the behaviour, than by trying to change the person.

In individuals where language deficits are the most prominent symptoms, difficulty understanding others or being understood by others may result in frustration. Simple, rather than complex, commands or instructions and the use of simple words are likely to improve comprehension. Use of visual supports, such as drawings or photos, may also be helpful in situations where verbal expression is disrupted.

Individuals with frontotemporal dementia frequently have executive function and reasoning deficits. “Reasoning” refers to mental activities that promote decision-making. Being able to categorize information and to move from one perspective of a problem to another are examples of reasoning. “Executive functions” is a term that refers to yet another group of mental activities that organize and plan the flow of behavior. A good example of executive functions is what might happen if one were driving a car, talking with the passenger and suddenly having to respond to a child running into traffic. The ability to handle all the stimulation and to quickly plan a course of action is accomplished via executive functions. Individuals with frontal lobe dementia often lack flexibility in thinking and are unable to carry a project through to completion. Failure of executive functions may increase safety risk since they may not be able to plan appropriate actions or inhibit inappropriate actions.

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia:

Impairments in social skills

– inappropriate or bizarre social behavior (e.g., eating with one’s fingers in public, doing sit-ups in a public restroom, being overly familiar with strangers)

– “loosening” of normal social restraints (e.g., using obscene language or making inappropriate sexual remarks)

Change in activity level

– apathy, withdrawal, loss of interest, lack of motivation, and initiative which may appear to be depression but the patient does not experience sad feelings.

– in some instances there is an increase in purposeless activity (e.g., pacing, constant cleaning) or agitation.

Decreased Judgment

– impairments in financial decision- making (e.g., impulsive spending)

– difficulty recognizing consequences of behavior

– lack of appreciation for threats to safety (e.g., inviting strangers into home)

Changes in personal habits

– lack of concern over personal appearance

– irresponsibility

– compulsiveness (need to carry out repeated actions that are inappropriate or not relevant to the situation at hand.

Alterations in personality and mood

– increased irritability, decreased ability to tolerate frustration

Changes is one’s customary emotional responsiveness

– a lack of sympathy or compassion in someone who was typically responsive to others’ distress

– heightened emotionality in someone who was typically less emotionally responsive

How is the diagnosis established?

Consulting a doctor to obtain a diagnosis at an early stage is critical. A complete medical and psychological assessment may identify a treatable condition. A number of conditions exist that produce symptoms similar to dementia. These include vitamin and hormone deficiencies, depression, overmedication, infections and brain tumours. If the symptoms are caused by dementia, an early diagnosis will mean early access to support, information, and medication.

It is important that anyone with suspected dementia has a thorough assessment by a neurologist, geriatrician or psychiatrist with a special interest in dementia to establish the diagnosis. Another option is to attend a memory clinic. A referral can be obtained from a general practitioner. A typical work-up is likely to include the following:

Detailed medical history. If possible, this history ought to be provided by the person with the symptoms and a close relative or friend. Medical history helps establish the onset (sudden or insidious) and progression of the symptoms (fast or slow). Often, behavioural changes are more apparent to family and friends than to the person with dementia.

Thorough physical and neurological examination. Usually this examination includes tests of the senses and movements to rule out other diseases and to identify medical conditions which may worsen confusion associated with dementia.

Laboratory tests. These blood and urine tests are sometimes called a ‘dementia screen’. They test for a variety of possible illnesses which could be responsible for the symptoms such as an under-active thyroid gland or vitamin B12 deficiency.

Brain imaging. Imaging of the brain is mandatory in all younger adults with suspected dementia to rule out reversible causes such as a benign brain tumour or hydrocephalus (fluid on the brain) and to look for patterns of brain changes associated with the specific types of younger onset dementia, such as local shrinkage (atrophy) of the frontal lobes in frontotemporal dementia. Computerised Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are forms of structural imaging methods that are widely available. In some specialist centres, structural imaging may be supplemented by functional imaging (SPECT or PET), which show how the brain is working.

Psychiatric assessment. This investigation helps identify treatable disorders such as depression, which can mimic dementia. It also helps to identify and manage symptoms such as anxiety or delusions which may occur in conjunction with dementia.

Neuropsychological assessment. Tests of cognition are administered to identify retainedabilities and specific problems in areas such as memory, comprehension, visual abilities, problem solving and numerical skills. These results can help with determining the diagnosis.

Persons with this form of dementia may look like they have problems in almost all areas of mental function. This is because all mental activity requires attention, concentration and the ability to organize information, all of which are impaired in frontal lobe dementia. Careful testing, however, usually shows that most of the problems stem from a lack of persistence and increased inertia.

Psychosocial Issues

The psychological, social, family and financial issues that affect individuals with frontotemporal dementia are drastically different from those that affect individuals with Alzheimer’s type dementia. When dementia occurs earlier in life, issues such as working, teenage children and financial stress are different from the issues dealt with by individuals who are older and most likely retired. Planning for the family’s financial security and for the education of children becomes a difficult prospect when an individual is faced with a dementing illness in the prime of his/her working career. The nature of the symptoms themselves are often embarrassing to family members and there may be loss of friends and other sources of social support. Finally, most adult day programs and residential care facilities are not equipped to address the special needs of the younger patient, especially if the behavioral symptoms are difficult to manage. As more is known about the disease, more policy changes may come into effect. Some residential care and adult day programs are recognizing the needs of the younger dementia patient and are beginning to offer services to meet their needs. Before making any decisions, it is best to investigate your options.

Depending on severity, a patient with impaired comportment may not be able to manage their daily activities without supervision. They may be at risk for harming themselves or being victimized because they would not be able to recognize their limitations or use proper judgement. Driving is usually unsafe for persons with this diagnosis.

Fortunately, there are steps that can be taken to provide a secure environment for the diagnosed person and obtain help for family:

Obtain a psychiatric evaluation from an individual with experience treating people with dementia. Certain medications can help with behavior problems such as agitation and hostility.

Share information with family and friends. This will help them better understand the patient’s behavior and provide an opportunity for them to offer the diagnosed persona and their family some support and respite.

Encourage the person to attend an early stage support group. Even if the support group is geared toward the person with early Alzheimer’s disease, much information will also be relevant to Frontal Lobe Dementia.

Meet with an attorney or financial consultant. Make sure Durable Power of Attorney forms have been completed for both health care and finances. Give copies to your doctor. An “elderlaw” attorney who is well-versed in these issues is still an appropriate choice to help you draft these documents or you may obtain the forms at many stationary stores and complete them on your own.

Attend a caregiver support group. Listening to others who are going through similar experiences can be very comforting. They may also aid you in developing new caregiver techniques and learn about different resources within your community.

Try to remain physically and mentally healthy. Be sure to get regular health check-ups for both the diagnosed person and family. Exercise and eat nutritious meals. Build in time for things that allow you to rejuvenate.

Obtain a driving evaluation: Contact your local Alzheimer’s Association for the driving evaluation program near you.

###

Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center

Contact Northwestern University